Discovery and Settlement

In the latter half of the seventeenth century, few explorers in Virginia ventured beyond the New River (Digital Commonwealth Anville: 1771 Map). According to Johnston (1906:9), “Captin Henry Batte in 1666, Thomas Batte and party in 1671, John Sailing…. in 1730, Salley, the Howards and St. Clair in 1742, Dr. Thomas Walker, and his parties in 1748-1750 are the only white men to have seen or crossed New River… prior to 1748.” The D’Anville 1755 map (Figure 2) shows the approximate location of the New River and Walker’s Settlement. In 1671, Major General Abraham Wood commissioned Thomas Batts and Robert Fallom’s journey which became known as the Batts-Fallom expedition. Wood was a trader in Richmond, and was looking for further economic ventures to open up trade with natives. The expedition traveled as far as present-day West Virginia (Brown 1937:503). Travel beyond this point was sporadic for the next few years.

Figure 2 1755 North America from the French of Mr. D’Anville Map, (Adapted with scale from Jeffery 1755)

According to Brown (1937:506), southwestern Virginia was first designated as a county in 1716. At that time, Governor Spotswood claimed the discovered land for the British Crown, joining it with Essex County and leaving the western border undefined (Brown 1937:506). In 1721 the land was divided in two. The western county was named Spotsylvania County while the eastern county remained Essex County. Spotsylvania was divided in 1734 into Orange County (Brown 1937:506). The Orange County boundaries as recounted by Brown, detail the amount of land considered to be a part of western Virginia at the time. As Brown describes it:

Orange County included ‘all the territory of land adjoining to, and above said line, bounded southerly, by the line of Hanover County, northerly, by the grant of the Lord Fairfax, and westerly by the utmost limits of Virginia (and that included all the land north and west to the Great Lakes, and the Pacific Ocean) (Brown 1937:506-7).

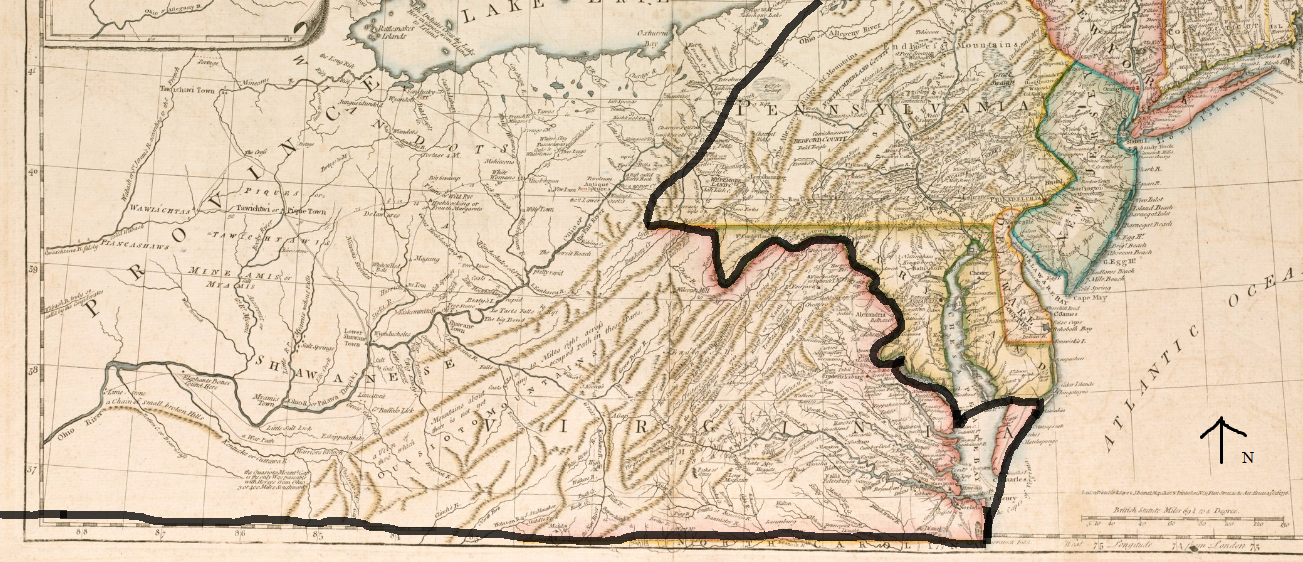

The land was divided again in 1738 from Orange County into Augusta and Fredrick Counties, with Augusta County encompassing the western region including the southwest border of Virginia (Brown 1937:507). The large expanse of land considered to be part of the Virginia Colony is outlined in black in Figure 3, on a 1776 British colonel map, and as Brown (1937:506-507) states the colony continued west to the Pacific Ocean.

Figure 3 1776 General Map of British colonies, in America and adapted from Governor Pownall’s late map 1776 (Pownall 1776)

Despite these divisions there were still large land grants and parcels awarded to high-ranking state officials. As Brown notes (1937:507) “in 1745 Colonel James Patton, county lieutenant and commander of militia for Augusta County, was granted by the governor and Council of Virginia one hundred and twenty thousand acres of land to the west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.” In order to survey and map out the land, Colonel Patton put together an exploration and surveying party. The group of explorers on this expedition included Dr. Thomas Walker, Colonel James Patton, Colonel Jon Buchanan, Colonel James Wood, and Major Charles Campbell (Brown 1937:507). It began in 1748 and its task was “locating and surveying valuable tracts of land, included in Colonel Patton’s land grant” (Brown1937:507). The first written records of exploration into southwestern Virginia territory were by Dr. Thomas Walker in 1748 as a part of this expedition (Brown 1937:507). The trip to survey Colonel Patton’s 120,000 acres allowed Walker to make important connections he would use later to bring settlers and development to the region as a part of a land company he helped to establish in 1749.

During 1749, two major land companies, the Ohio Land Company and the Loyal Land Company, were established and awarded large tracts of land by the Governor and Council of Virginia (Brown 1937:508). The Loyal Land Company was awarded 800,000 acres of land in Southwestern Virginia region and “was composed of 46 gentlemen, among whose members were John Lewis and Thomas Walker” (Brown 1937:508). Walker led an expedition with five companions “to locate a boundary for 800,000 acres in the western reaches of Virginia suitable for settlement” (Kincaid 2005:43). This expedition for the “Loyal Company” began at Walker’s home in Albemarle County, Virginia and continued through parts of West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and to the Cumberland Gap (Brown 1937:509). Dr. Walker made several written entries on his trip describing the numerous places through which his expedition passed. On April 13, 1750, Walker penned the first written record of Cave Gap, later renamed Cumberland Gap (Kincaid 2005:47):

On the North side of the Gap is a large Spring, which falls very fast, and just above the Spring is a small Entrance to a large Cave, which the Spring Runs through, and there is a constant stream of Cool air issuing out….On the South side is a plain Indian Road.(Kincaid 2005:47-48)

Future use of the Gap would allow for expansion west and access across the Appalachian Mountains. Robert Kincaid, in his book The Wilderness Road, describes Walker’s find further: “the sharp break in the high mountain wall on the western rim of the Appalachians was the gateway through which hundreds of thousands of people would pass on their way to the limitless west” (Kincaid 2005:48).The Indian road mentioned by Walker was later known as Wilderness Road and in time would be expanded, retraced, and widened.

According to Ralph Brown, “by the end of 1754, Dr. Walker and his associates had surveyed and sold 224 tracts of land, at three pounds per hundred acres, in Southwest Virginia, containing more than 45,000 acres, many of which tracts were occupied by settlers” (Brown 1937:509). While some settlers had already migrated into the Shenandoah Valley, Walker’s exploration to find a suitable place for westward expansion did not immediately result in a rapid increase in settlement. According to Kincaid, “The French and Indian War, soon to engulf the border, would halt for more than a decade the settlements advancing over the Appalachian divide from the Great Valley” (Kincaid 2005:52). A 1755 map titled “North America from the French of Mr D’Anville: Improved with the back settlements of Virginia Course of Ohio” (Figure 2) from the Boston Public Library Digital Commonwealth collection corroborates these written accounts through the clearly defined “Walkers Settlement 1750” marked along the “Cumberland or Shannomen’s River” as highlighted by the yellow star.

During the French and Indian War, Robert Dinwiddie was succeeded by Jeffery Amherst as the Governor of Virginia in 1759 (McAnear 1950:196). Jeffery Amherst’s governing duties were carried out by his appointed Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier because Amherst was serving as general in the war. This left Lord Amherst free of obligation to the colonies (McAnear 1950:197). Following his death in 1768, Fauquier was succeeded as Lieutenant Governor by Norborne Berkeley (William and Mary Quarterly 1900). Governor Berkeley died in 1770, leading to the appointment of John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, as Governor of Virginia (Horne 1975:176). These rapid political changes made consistent regulation of the hundreds of westbound settlers difficult and allowed more settlers to move beyond the 1763 boundaries.

The French and Indian War (1754-1763) resulted in Great Britain’s control of all land located east of the Mississippi River (Brown 1937:510). Following the end of the war, the British, who were unwilling to antagonize hostile Indians occupying the land surrounding the Ohio River, issued The Royal Proclamation of 1763 (Morgan 2007:131). This proclamation forbade settlement west of the Blue Ridge and according to Hagy (1967:410) was ignored by settlers’ eager to survey land tracts sold by the Loyal Land Company. Despite the changes in political administration in the Commonwealth of Virginia that occurred between 1759 and 1770, more settlers were pushing westward far beyond the Blue Ridge Mountain boundary.

In late April or early May of 1769, Joseph Martin of Albemarle County, Virginia, acting as an agent for Dr. Thomas Walker, began an expedition to Powell’s Valley, in what was then Russell County, Virginia (later to become Lee County) in return for a land grant from the Loyal Land Company (Kincaid 2005:74). Determined to build a fort farther west, Martin’s group built Martin’s Station near present-day Rose Hill, Virginia. The 1769 settlement of Martin’s Station was the first attempt of a permanent settlement and was the westernmost settlement at that time (Morgan 2007:96). The fort was named after its leader Joseph Martin and was inhabited for only a few months because of attacks by Cherokee Indians (Brown 1937:506). The area was already the center of Cherokee and Shawnee disputes and the creation of Martin’s Fort only escalated the situation (Brown 1937:506). The fort was attacked, as a result of poor relations and its location, shortly after completion and this forced Martin to return to Albemarle County. Martin suffered heavy financial losses as a result of deserting the fort and did not return to the Gap until six years later.

Daniel Boone arrived sometime around late May of 1769; this was only a short time after Martin had started to build Martin’s Station and only weeks before the Indian attacks that would force Martin to retreat (Draper 1998:210). Boone’s small party was a part of a two-year hunting and exploration trip which did not expect Martin’s small fort so far west of other settlements (Kincaid 2005:74). After leaving Martin’s Station, Morgan (2007:95) states “Daniel Boone, John Findley, and John Stewart with three assistants crossing the Clinch and then Powell’s River then turned north through Ouasiota or Cave Gap which Dr. Thomas Walker or others had named Cumberland Gap.” Boone traveled through the area on several occasions both as a guide and on hunting trips. Boone was an important figure in the development of Lee County because of his involvement in establishing western settlements and clearing Wilderness Road for travel during the 1770s.

He departed on his next trip into present-day Lee County on September 25, 1773 leading a group of potential settlers to Kentucky (Draper 1998:285). On October 9, 1773 James Boone, Daniel Boone’s oldest son, James Boone, and a small group attempted to meet Daniel Boone’s larger party of settlers on their way to establish a settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains (Draper 1998:287). James Boone decided to camp along the trail near the junction of Wallen’s Creek and the Powell River and (unknown to James) about three miles from his father’s camp (Draper 1998:287). During the night Boone’s son was killed by a group of Shawnee Indians who ambushed and tortured the small party. Only a few escaped (Draper 1998:288). The bodies were discovered the next morning by Captain Russell, whose son Henry was among the dead, and Captain David Gass, both of whom were going to join Boone’s group of settlers (Draper 1998:288). The expedition was halted and a general council of Daniel Boone’s party was held after the discovery of the Shawnee attack (Draper 1998:288). Boone wished to continue on to Kentucky; however, the other settlers voted against him, fearing more encounters with other native groups (Draper 1998:290). Boone accepted Captain David Gass’ offer of a temporary residence for him and his family on Gass’ farm in Castle-Wood in a neighboring Virginia county (Draper 1998:290). According to Draper (1998:290) “Boone was, most likely, induced to this step by the hope of being joined the ensuing spring by Captain Gass and Captain Russell in another attempt to permanently occupy Kentucky.” However, that did not happen and it was not until 1775 that Boone was able to organize a large group to settle in what was named Kentucky County in 1776 (Morgan 2007:136-138).

The attack on Boone’s son and his party had wider national repercussions. Other native groups particularly in the Ohio Valley had been attacking settlers (Morgan 2007:139). News of these attacks sparked unrest appearing in the colonial newspapers in December of 1773 (Morgan 2007:140). The news of the Boone party attack the following spring heightened these fears. In response to these attacks, the Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, secured funds for what would become known as Lord Dunmore’s War. According to Draper’ (1998:291), “in his speech at Fort Pitt, Dunmore charged the murder of young Russell and his companions as having been chiefly perpetuated by the perfidious Shawnees and enumerated it among the chief causes that led to the Indian War of 1774.” The war resulted in the movement of the Shawnee border past the Appalachian Mountains and onto the banks of the Ohio River (Calloway 2007:51). Lord Dunmore’s War decreased the settlement and exploration in southwestern Virginia until 1775 because many of the noted explorers, such as Boone, were fighting in the war. On October 10, 1774, after the conclusion of the battle at Point Pleasant, the eastern Indian border was redefined and set at the edge of the Ohio River (Calloway 2007:51). The clearing of land from Virginia to the Ohio River allowed settlers to further their westward migration and initiated the establishment of more permanent settlements (Calloway 2007:51).

In addition to the concerns with native attacks, Virginia colonists had growing concerns with the increasingly invasive British policies (Badertscher 2015:2). In September of 1774 a group of Virginia statesmen met to discuss the issues and this discussion became known as the First Continental Congress, which began the establishment of an American governing body separate from British rule (Badertscher 2015:2). As the year progressed, events in eastern Virginia and the other colonies slowly escalated into the American Revolution. Once again, high political tensions resulted in an increased focus on westward expansion in Lee County and this expansion was marked by several key events.

The first few months of 1775 brought new settlements to the Cumberland Gap area (Morgan 2007:159). Joseph Martin made his second attempt to settle near present-day Rose Hill, Virginia during the first months of 1775 (Kincaid 2005:101) reestablishing Martin’s station in Powell Valley and building relationships with local native groups. March of 1775 brought the official sale of land from the Cherokee nation to the Transylvania Company’s main mediator, Richard Henderson (Morgan 2007:160) which occurred at Martin’s Station. On March 17, 1775 native representatives and leaders Chief Oconostota and Dragging Canoe, sold Henderson “the additional land between the Holston River and Cumberland Gap as a ‘path deed’ to reach the lands he had already purchased” ( Morgan 2007:162). The agreement reached by Henderson and the Cherokee was meant to help secure the safety of settlers in the area; however, the land was controlled by several native groups that were not included in the sale agreement and therefore the agreement did not guarantee safe passage. As Brown (1937:506) states:

If the settlers of Southwestern Virginia had been deliberately looking for Indian trouble, they could not have done better than they did, grouping together on centuries-old Indian trails, in a region disputed as a hunting ground by the Cherokee and Shaw- nee Indians, and over-lorded by the Five Nations (the Iroquois), the fiercest and most powerful of the tribes of North America. (Brown 1937:506)

Also in March of 1775 Martin and Daniel Boone met again when Boone, (Draper 1998: xvii) who had been hired by the Transylvania Company, arrived in the region to lead a company of men with the purpose of widening the warrior’s path through the Gap to increase the settlement in Kentucky County, Virginia. The path, little more than old Indian trails, was cleared for settlers and renamed the Wilderness Road. Boone led subsequent groups of settlers through the Cumberland Gap and founded Boonesborough, Kentucky in May 1775 returning to the Clinch River in June to bring his family through the Gap (Draper 1998: xvii). Martin and Boone’s historic settlement advances in 1775 were crucial to the development of southwest Virginia and Kentucky.

Also during this time of significant settler expansion in southwestern Virginia the American Revolution began in April of 1775 less than a month after Daniel Boone arrived to widen the Warrior Path into the Wilderness Road (Draper 1998: xvii). July 4, 1776 marked the official separation of American colonies from Great Britain with the Declaration of Independence (Badertscher 2015: 3). The American Revolution created a shifting government and ever-changing land regulations for the western edge of the colonies. After the end of the war, the official adoption of the Articles of Confederation did not take place until 1787 at which point public records, requests, and notices begin appearing before the newly established Virginia General Assembly (Brown 1937:507). In 1786 in southwest Virginia, Russell County was formed out of Augusta County, which had been slowly breaking up into numerous smaller counties as state lines were formed and decided (Brown 1937:507).The newly-organized nation proceeded to induct states into the Union and the tenth state to be inducted was Virginia in 1788. Not long after Virginia’s incorporation Kentucky was added to the union, in 1792 becoming the fifteenth state (Draper 1998: xix).

A new western county was carved out of Russell County in 1793 (Brown 1937:507) and was named Lee County in honor of Henry “Light Horse” Harry Lee (Gannett 1905:184). Lee was from a prominent Virginia family and had served in the Revolution as a cavalry officer in the Continental Army and then as a Major General in the U.S. Army (Royster 1981: 41,139). Lee also later played a major role in the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 (Royster 1981:137). Lee retired from military service and became the ninth Governor of Virginia in 1791 after a successful term of office in the Virginia Assembly (Royster 1981:14). During his tenure as governor, Lee dealt with many Indian conflicts in western Virginia (Royster 1981:125-126) Lee’s work to secure settlers’ safety in the western corner of Virginia was acknowledged when the westernmost county of Virginia was named after him (Royster 1981:126).

The new county lacked a location to conduct court business and in 1794 put forth a petition to the General Assembly which asked that Fredrick Jones’ land be used for court proceedings (Appendix A). Jonesville, the first official township, was named the county seat in 1794 after the approval of the petition. The petition also included signatures of many of the 1794 residents (Appendix A). At that time, the county also included the geographical areas of present-day Scott and Wise Counties. These counties were not yet separated from Lee, Russell and Washington Counties and wouldn’t be until the nineteenth century.

After Jonesville was named the county seat, Governor Shelby of Kentucky hired Joseph Crockett and James Knox in 1796 to widen and improve the Wilderness Road marked by Boone in 1775 (Kincaid 2005:189-191). Crockett and Knox redefined the exact path and officially named the road “Wilderness Road,” separating it from Boone’s original path which was then known as Boone’s Road (Kincaid 2005:189-191). Although the path served as a main road through Lee County it was not the only road in existence. Petitions from the 1790s brought by inhabitants of Lee County to the General Assembly of Virginia requested funds and the appropriation of taxes to build or maintain roads throughout the county. As the nineteenth century began in Lee County, more and more people called Powell’s Valley home and even more people passed through, moving westward on Crockett and Knox’s new Wilderness Road.

© 2017

Martha Grace Lowry Mize

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED